Rust for the Rustless

It has been a while. I hope you have not missed me! It seems that Rust is gaining steam and more people are starting to use it for building trading platforms. I have been advising people in the most tactless way possible that their life would be better if they embrace the crustation. So here we are. I have about two years of Rust experience under my belt, Although time is not the only measure of ability. There are some very “Rusty” ways to do things that are good to know about when you first start. As I have become more experience with Rust there are some common problems that I have found myself refactoring a lot. This article is a list of some of the main things I wish I knew when I started and also some helpful resources to help you on your Rust journey.

Avoiding Unwraps Everywhere

Rust makes everything explicit. It also often makes you think

what if this doesnt work?Are you sure the key is in the map?

Many functions in Rust return Options or Results. You cannot use them directly, so to get at the value in them, you can use unwrap(). At first it is temping to unwrap everything.

let lookup: HashMap<u32, &str> = HashMap::from([(1, "Binance"), (2, "Okex")])

let name = lookup.get(&1).unwrap();

The issue is if the Option is None, or Result is Err, the program panics. Using unwrap is often tempting as one of the correct ways to deal with Options is to use the match statement to check the type. Using match is quite verbose, and often you only want to deal with the happy case.

let lookup: HashMap<u32, &str> = HashMap::from([(1, "Binance"), (2, "Okex")])

match lookup.get(&1){

Some(name) => { println!("{}", name); }

None => { /* error handling */ }

}

So it is temping to just use unwrap everywhere to avoid the boilerplate, but eventually you will get really unstable code due to the code panicking caused by this.

The solution to this is using If let

let lookup: HashMap<u32, &str> = HashMap::from([(1, "Binance"), (2, "Okex")])

if let Some(name) lookup.get(& 3) {

println ! ("{}", name);

} else {

eprintln ! ("What are you doing?");

}

or it is possible to give defaults to unwrap so that it is able to deal with the cases where it would otherwise return None

let lookup: HashMap<u32, &str> = HashMap::from([(1, "Binance"), (2, "Okex")])

if name = lookup.get(&1).unwrap_or("NA");

println!("{}", name);

Pattern Matching

Where this gets quite neat is dealing with situations where you have many optional variables. So in the example

let A_opt = Some(4);

let B_opt = Some("cat");

let C_opt = Some(3.14);

println!("a: {} b: {} c: {}", A_opt.unwrap(), B_opt.unwrap(), C_opt.unwrap());

Using multiple unwraps is just bad.

You could have an early exit, or a series of early exit checks.

if A_opt.is_none() || B_opt.is_none() || C_opt.is_none() { return }

println!("a: {} b: {} c: {}", A_opt.unwrap(), B_opt.unwrap(), C_opt.unwrap());

This will at least not panic, but it is still kind of garbage as you are not really dealing with the edge cases.

A better solution is using match and pattern matching to be able to deal with different combinations

match (A_opt, B_opt, C_opt) {

(Some(a), Some(b), Some(c)) => {

println!("a: {} b: {} c: {}", a, b, c);

}

(a, b, c) => {

if a.is_none() { eprintln!("A is none"); }

if b.is_none() { eprintln!("B is none"); }

if c.is_none() { eprintln!("C is none"); }

}

}

So the above code allows the different cases to be dealt with separately if needed and the happy case to be simply defined.

Be Careful of Syntactic Sugar

I was once using a convenient method to avoid having multiple constructors if only a subset of fields are to be set.

struct MyStruct {

id: u64,

a: f64,

b: f64,

c: f64,

}

To create an object if you maybe want to create a default object but set the id to a specific value

let obj = MyStruct{id: 007, ..Default::default() };

I originally thought the compiler would be smart enough to realize that if you are defaulting a value, it does not need to be created in the call to Default::default(). This is not the case. A complete default object is created, then the field(s) in question are overwritten. If there is a type that is not a primitive or the default is expensive, this can be expensive.

The alternative I use is to have specific constructors.

impl MyStruct {

fn new_with_id(id: u64) -> Self {

MyStruct { id, a: 0.0, b: 0.0, c: 0.0 }

}

}

// create obj

let obj = MyStruct::new_with_id(007);

This avoids any duplication at runtime and can be much more efficient.

Error Chain

When doing a lot of parsing, database and other things, you will come across Result<T, E> a lot. This is used in cases where operations can fail. The database is not available, the json string is malformed etc. Results have two enum types like Option’s Some and None. Results types are called Ok and Err and the techniques above regarding if let can be used for results.

fn connect_to_database()->Results<Connection, DatabaseErr> { /*impl */}

if let Ok(conn) = connect_to_database {

if Ok(results) = conn.run_sql("select * from who_let_the_dogs_out") {

println!("{:?}", results);

}

}

The thing that is tricky with Rust’s type systems is if you want to pass the errors out of the function. Say you want to connect to a database, parse the result and maybe do your own processing. There are 3 types of errors that can happen DatabaseError, ParserError, and MyError. So if the return type is Result<T, E> what is the type of E? This can be painful, but it is what the error_chain crate solves. Its solution is to map errors from other packages to a homogenous error type from your crate. Then no matter what error is created in the method, the Error type in results will be the Crate error.

With error_chain crate the example is below

use errors::*;

fn my_fun() -> Result(MyType) {

let conn = get_connnection()?; // ? passes the DatabaseError to the caller and error chain wraps it

let res = conn.get_data()?; // pass any DatabaseError to caller (wrapped by error chain)

let raw_value = parse(res)?; // pass any ParserError to caller (wrapped by error chain)

let value = process(raw_value)?; // pass any crate error to caller (wrapped by error chain)

Ok(value) // return result

}

// calling the function

match my_fun() {

Ok(value) => { println!("{}", value);}

Err(e) => { /* e is the wrapped type given by error chain */}

}

The above code is often so much neater than having to explicitly deal with all the reasons that the code could fail in the method. The error type is also only wrapped, so if you want to write error handling logic for the specific error reason, this is also easy to do.

Doc Tests

When writing documentation, it is normal to include code examples.

/// Squares a given number.

///

/// # Examples

///

/// ```

/// let x = 5;

/// let squared = square(x);

/// assert_eq!(squared, 25);

/// ```

fn square(x: i32) -> i32 {

x * x

}

One thing that is very neat about cargo test is it will compile and run the examples in doc strings.

Over time as you refactor often the examples get broken as method signatures change.

So Rust doc tests prevent this by raising an error if the examples no longer work.

Clippy

Clippy is a linter that checks for common issues. Lints are grouped to make it easier to decide if they should be a compiler error or just a warning.

clippy::pedantic: This lint group includes all the lints that Clippy developers consider pedantic. These lints may catch potential issues that are less common or subjective, but they can help improve code quality.

clippy::style: This group includes lints that enforce coding style guidelines. It focuses on stylistic aspects of your code, such as naming conventions, formatting, and idiomatic patterns.

clippy::correctness: This group includes lints that check for correctness issues in your code. These lints help catch potential bugs, logic errors, or undefined behavior in your code.

clippy::complexity: This group includes lints that check for overly complex code or constructs that can be simplified for better readability and maintainability.

clippy::perf: This group includes lints that check for performance-related issues in your code. It helps identify inefficient code patterns or operations that can be optimized for better performance.

clippy::cargo: This group includes lints related to Cargo, Rust's package manager. It checks for issues related to dependencies, build configuration, and package metadata.

clippy::nursery: This group includes experimental or unstable lints that are still under development or evaluation. These lints may change or be removed in future releases of Clippy.

This can be added to lib.rs main.rs of the crate

#![deny(clippy::perf)]

#![warn(clippy::pedantic)]

It is also possible to set specific lints in case lower granularity is needed

// this has caught bugs where I did == instead of =

#![deny(clippy::bool_comparison)]

to run clippy you can use

cargo clippy --all-targets --all-features

No inheritance

Rust uses composition rather than inheritance. Inheritance if you come from languages like Java seems like a nice idea, but it is prone to bugs. It is better to explicitly define the behaviours of each struct to avoid code being magically added or changed as superclasses are modified. I worked on some java code once where the inheritance structure was about seven layers deep, and some methods were removed in one layer and added back in the next. Trying to work out what code was actually running in the seventh layer was pretty much impossible.

This is why Rust avoids abstract classes completely.

Rust is Explicit

This can seem annoying at first.

It comes up a lot when casting types and working with f64 and f32 types.

Rust makes you think about overflows and truncation errors when other languages might just swallow them.

You should avoid using as if you can as it can mask conversion errors. Functions like into() or try_into() and checked_sub() provide safety when doing these types of operations.

Access Control and Visibility

Access Control is achieved via pub, pub(crate). The compiler also checks for leaking of information i.e. you cannot have a pub variable in a pub(crate) struct.

pub struct MyStruct {

pub name: String, // public name

pub(crate) id: u64, // only used withing the crate

var: f64, // can only be used in the module

pub fn pub_fun() {}

pub(crate) fn crate_fun() {}

fn private_fun() {}

}

pub(crate) BadStruct {

pub name: String, // this is not allowed as the struct has lower access privileges

}

Tests are normally in the module i.e. file so that can make checking private variables easier. In other languages, this is more challenging. This can lead to the private variables being exposed so they can be checked within tests. This is a common testing anti-pattern. In general, private fields/methods should not be tested as it exposes the implementation and can make refactoring difficult.

Performance Benchmarking

So you have written some new code and want to know if it is awful. Or you just want to compare the performance of various libraries with a hand rolled solution to prove youre smarter than everyone else.

Criterion is a rust benchmarking library that makes this really simple to do. Just add this to cargo.toml

criterion = { version = "0.5.1", features = ["html_reports"] }

[profile.bench]

lto = true

opt-level = 3

codegen-units = 1 # improved benchmark reliability

[[bench]]

name = "hash_bench"

harness = false

This is an example benchmark test that can be placed in benches/hash_bench.rs.

use criterion::{black_box, Criterion, criterion_group, criterion_main};

use hashbrown::HashMap as HBHashMap;

use std::collections::HashMap as StdHashMap;

use fxhash::{FxHashMap};

fn map_fun1(map: &mut StdHashMap<i64, i64>) {

map.insert(3, 42);

}

fn map_fun2(map: &mut FxHashMap<i64, i64>) {

map.insert(3, 42);

}

fn map_fun3(map: &mut HBHashMap<i64, i64>) {

map.insert(3, 42);

}

fn hash_brown_test(c: &mut Criterion) {

let mut map: HBHashMap<i64, i64> = HBHashMap::default();

c.bench_function("hashbrown map test", |b| b.iter(|| map_fun3(black_box(&mut map))));

}

fn fx_map_test(c: &mut Criterion) {

let mut map: FxHashMap<i64, i64> = FxHashMap::default();

c.bench_function("fxhash map test", |b| b.iter(|| map_fun2(black_box(&mut map))));

}

fn std_map_test(c: &mut Criterion) {

let mut map: StdHashMap<i64, i64> = StdHashMap::default();

c.bench_function("std map test", |b| b.iter(|| map_fun1(black_box(&mut map))));

}

criterion_group!(benches, std_map_test, fx_map_test, hash_brown_test);

criterion_main!(benches);

To run the benchmarking it is as simple as running cargo bench.

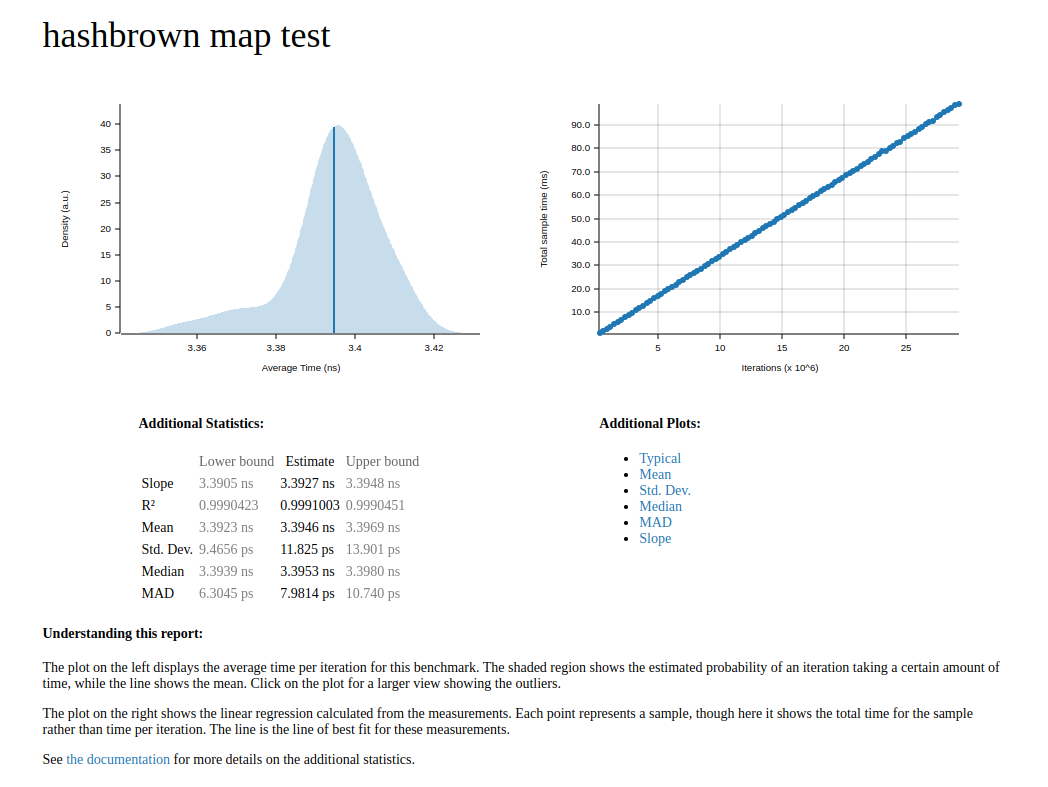

When the html reports feature enabled produces reports like this.

Html reports can be found in the target/criterion directory. The reports are useful to dig deeper into the latency distribution of the code under test. Criterion also monitors the performance during refactoring to warn if the performance of a function has improved or regressed.

Lifetimes Strings and &str

This is something that is really important for performance. The borrow checker can be a pain. Using strings should be avoided in general, that said, when they are used they should be used once. Since &str is a reference and not an object, it cannot be moved. For it to be borrowed, the borrow check must make sure you don’t yeet it somewhere else while the function is running. This is done via lifetimes. When you pass a reference it is bound to a lifetime.

struct Instrument {

instrument_id: u64,

symbol: &'static str,

}

fn main() {

// Create an instance of the Instrument struct

let instrument = Instrument {

instrument_id: 1,

symbol: "BTCUSDT",

};

// Access fields of the Instrument struct

println!("Instrument ID: {}", instrument.instrument_id);

println!("Symbol: {}", instrument.symbol);

}

In the above example the 'static tells the compiler that the str value will live for the length of the program.

If the &str is passed as an argument the compiler can attach the lifetime of the variable so that it can check that it outlives whatever it is passed to.

struct Instrument<'a> {

instrument_id: u64,

symbol: &'a str,

}

fn main() {

let symbol = "BTCUSDT";

// Create an instance of the Instrument struct

let instrument = Instrument {

instrument_id: 1,

symbol: symbol,

};

}

In this example lifetime 'a is generated by the compiler and used to make sure that the symbol outlives instrument;

Derive

When creating structs, a lot of behaviour can be added via the derive macro. Objects can be de-serialised just by adding a single line of code. It is also worth adding Default to your classed should you want to use them in a data structure.

use serde::de::DeserializeOwned;

#[derive(Deserialize, Debug, Default)]

pub struct ApiConfig {

pub key_map: HashMap<String, String>,

}

Macros

I actually am not a fan of these. I use simple ones as helper functions like

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! to_bps {

($x:expr) => {

$x * 1_00_00.0

};

}

let x_bps = to_bps!(0.0001);

They are incredibly powerful (like the derive macro) and have the ability to write code themselves like any other pre-preprocessor. Just Like C++ templating, I am not sure how easy it is to debug/fix heavily macroed code. This is just a preference thing. I’m sure if you know what you are doing you can do some really cool things with it.

ChatGtp

If you are coming from a different language, chatgtp can be a good way to learn about how to do things in Rust. You can give it some example code and ask it to port it to rust. It is not perfect, but it is a good way to learn about some topics like iterators, data types, filters, etc. It is also good at suggesting popular libraries. This is how I originally found out about Rayon and some of its benefits for async vs. tokio.

Materials

A Half An Hour To Learn Rust

This is a great introduction into some of the key concepts into Rust. The main thing is that its readable and very quick to absorb if you come from other languages. Most programming books and incredible terse and frankly just boring to read. So this concept is really clever to take the same content and make it palatable.

Rust Exercises

This course will teach you Rust’s core concepts, one exercise at a time. You’ll learn about Rust’s syntax, its type system, its standard library, and its ecosystem.

The Rust Programming Language

This is kind of the bible of Rust. That said, it’s boring and more of a reference book. I have not completely read it, I have only picked through sections such as error handling etc. I would still say its worth having in case you need to look things up.

Rust Brain Teasers

This book covers some of the leaky abstractions and weird ways that Rust does not really behave the way you might expect. It is good additional reading as you become more familiar with the language.

Rust Atomics and Locks

This is a very detailed book not only about Rust but how memory architecture works in multithreaded systems. Its also additional learning if you want to get deep into interprocess communication techniques like SeqLocks.